- April 25, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

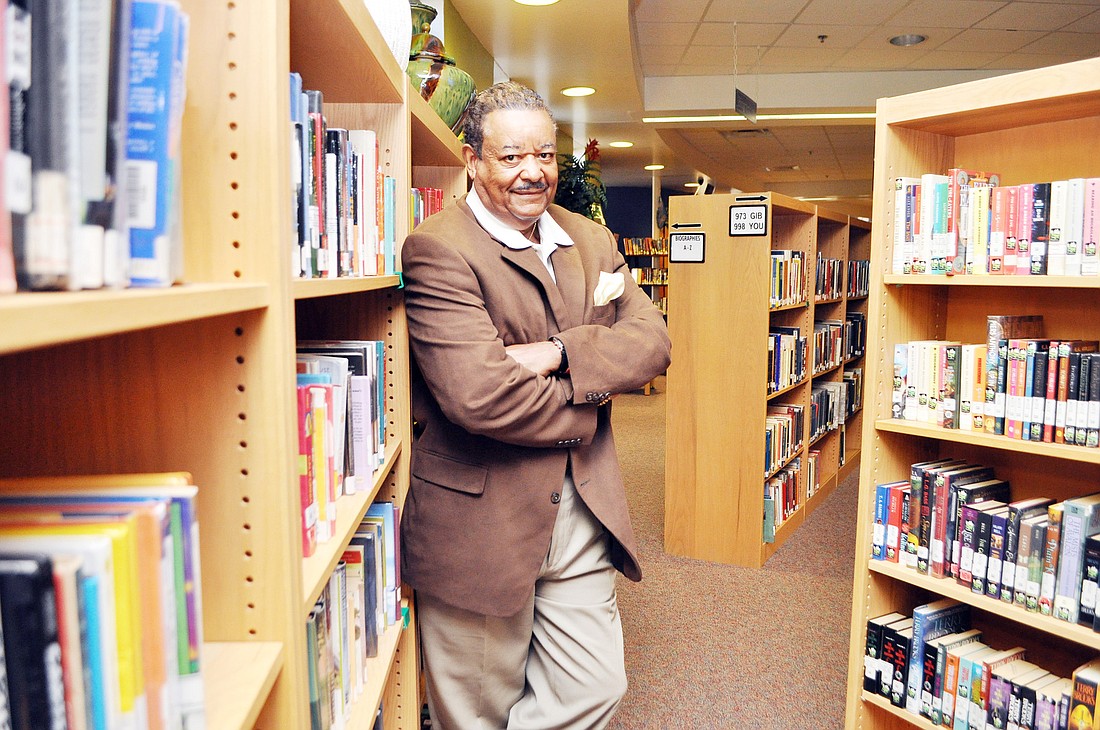

Leading mentor John Winston makes raising Flagler’s youth his business.

John Winston

Age: 74

Family: He and his wife of 44 years, Fanchon, have seven children and 35 grandchildren

Occupation: President of African American Mentor Society

Quirky fact: He sang with performer Kathryn Grayson at a fair, in 1965.

John Winston, president of the African American Mentor Program, believes in discipline.

He got his first job when he was 8 years old, scrapping metal and selling newspaper in segregated St. Louis. Before he could afford a real one, he made a makeshift drum set from hat boxes and a washtub kick pedal, and played on the street for coins. At 11, he operated a shoeshine parlor, which he owned with a friend after striking a deal with the property’s landlord.

Then in high school, he learned how to make men’s fedoras and started selling them to his teachers.

“I grew up in an environment of poor people, saw people living in boxes and fruit crates,” he said. “But I had a team of parents who cared enough (not to let that define me).”

His mother made him do his homework every day after school. Then she would ask about his day, and if he ever did something bad, he would tell her. Because back then, he says, the whole town looked after you. It was a village. Back then, he says, it was harder to slip through the cracks.

After high school, Winston got drafted. But, determined to get an education, he went to Washington and took a test to ensure entry into Navy academics.

“If you get an education, you can get out of this foolishness,” he said. “And we did.”

He got a job in cancer research, then in broadcast journalism and, eventually, he was offered a position by President Ronald Reagan in the U.S. Department of Transportation, where he led an $11.6 billion rail project.

He was appointed by Presidents Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton and George W. Bush to become the first African American to hold several high positions in federal departments.

Then, in 2003, he moved to Palm Coast.

“I came here — allegedly — to retire,” he said, sitting in a back room at Flagler Palm Coast High School, where he volunteers most of the week. “That didn’t work.”

Today, Winston leads a group of 42 men and 15 women in mentoring Flagler’s youth. He comes to FPC three or four days per week to meet with students, then spends his remaining time circuiting the county’s other schools, attempting to serve as a motivating force to children lacking one elsewhere.

“It’s been one heck of a ride,” he said of his life. “I owe so much. I have to give it back.”

Flagler Schools’ special projects coordinator, Sabrina Crosby, who has worked with Winston the past six years, says he sees mentoring as more than just a job after retirement. He sees it as a lifestyle.

“(He) is putting his heart and soul into changing lives,” she said. “He has led the charge in educating the community about the achievement gap that exists among our African American children. He has been relentless … (and) he sends a powerful message.”

Winston works with the underprivileged and the struggling. Through mentorship, he intends to rebuild the village of his childhood, where the community looks after the community, and everyone’s a parent.

At Thanksgiving, he had four children at his house for dinner, one of whom was homeless. In addition, he fed 12 others who wouldn’t have eaten otherwise.

When Winston speaks of his past, he does so objectively. He worked in the White House. He broke color barriers. He was an 11-year old entrepreneur.

Those are facts.

But when he speaks of his current work, his tone changes. He sounds proud.

“Terrence,” he said, sliding a photo across the table. In it, he’s shaking hands with a teenager wearing a graduation cap and gown. They’re standing in front of a banner for the Florida Youth Challenge Academy, smiling widely.

When he began mentoring Terrence, Winston helped him through middle school. Then he got him into the Linear Park program, an outdoors-based program where he could “learn about life external from the school,” and Terrence excelled.

Now, Terrence is doing 32 hours of weekly community service until he starts college.

Winston helped another mentee, Rashawn, raise his grade point average from 1.5 to 3.4 in three years. Rashawn is now attending Daytona State College.

Of 20 boys currently mentored at Flagler Palm Coast, results show 13 as making grade-point proficiency, which means they’re now scoring A’s, B’s and C’s, instead of D’s and F’s.

“I see it as a big vision,” Winston said of mentorship: “Educationally changing America for the better.”

It all started in Maryland, when he became involved in the Boy Scouts. He studied kids of all ages. “I saw their hearts’ desires. I saw their emotions. I saw their frailties,” he said. “And I said, ‘Wow.’”

He said that when many children get home from school today, their parents aren’t home. They let themselves in. They do whatever they want.

And that’s unacceptable.

“We’ve got to get up off our good intentions and start to best serve the needs of our children,” he said. “You can’t expect the school districts to do it alone. … If the village elders don’t come full circle, then the village idiots will start educating their children.”

After signing contracts with mentees, Winston is involved until his pupil graduates high school, enters college, signs with the military or gets a job. Mentorships usually last about 14 months.

“We’re giving up on stern, hard, fought for and achieved academic standards. We can’t give up on them,” he said, tapping his forehead. “We have to reinforce the brain.”

Winston takes out a postcard of a baby looking amazed, eyes wide, brows raised, mouth curled into a ring of astonishment. He calls it the “wow” factor, and it’s at the heart of what he’s trying to accomplish in Flagler.

Get kids excited about learning. Surprise them with what they’re capable of.

“There were no ‘wows’ for me; every day I grew up was survival,” he said. Then he patted the photo on the table, and paused. “(But) if I can just achieve this (effect). … I have this fire in my belly about making a child do this.”