- April 19, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

by: Brent Foster

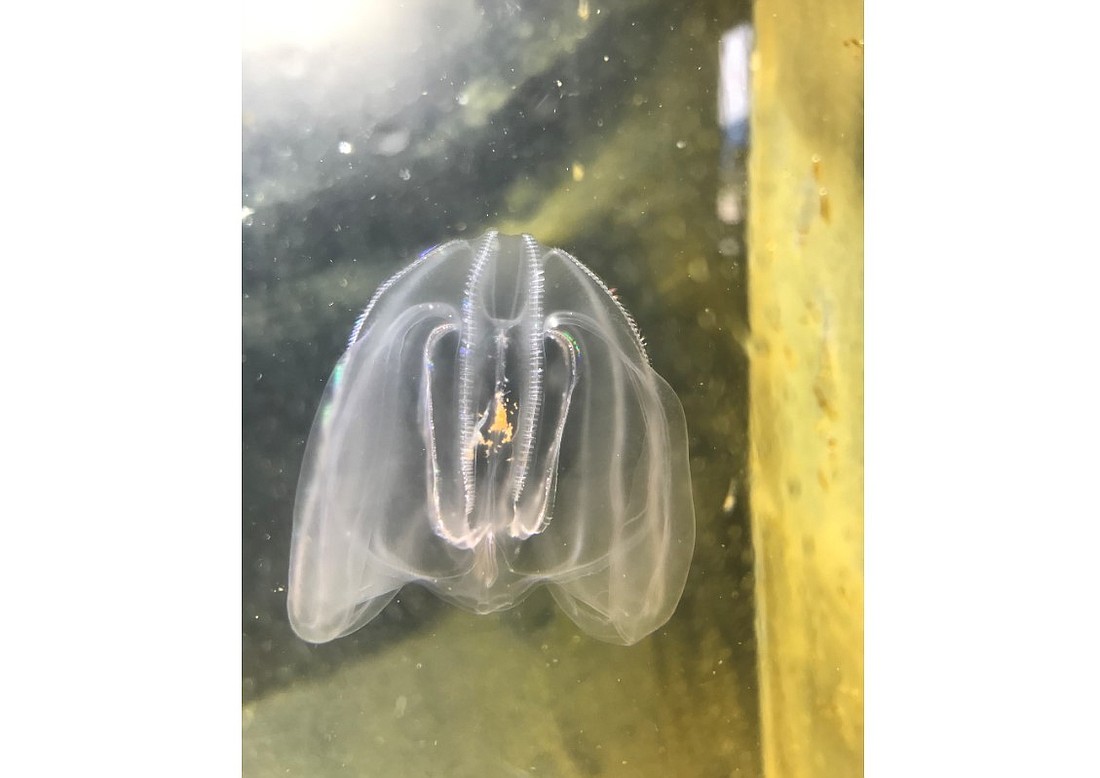

Ctenophores, or comb jellies, might not look like much. Picture a translucent gelatinous orb about the size of a golf ball, strung with a kaleidoscope of wriggling colors refracting light. Now imagine being cut in half and then having both halves grow back, good as new. This regenerative ability may sound like science fiction, and for you and me it is (at least for now). But to these “simple” animals, regeneration after an injury is part of everyday life.

You might mistake these creatures for jelly fish—you may have seen them floating in the Matanzas Inlet near the Palm Coast Marina. At least that’s where Dr. Allison Edgar goes to catch Mnemiopsis leidyi, aka the warty comb jelly or the sea walnut.

Edgar is a post-doctoral scientist at the Whitney Laboratory for Marine Bioscience, a research institute of the University of Florida located on the border of Flagler and St. Johns counties. She researches evolution by comparing the development and regeneration of Mnemiopsis and Beroe ovata, a member of the so-called cigar comb jellies. Her research is funded by the National Science Foundation.

Edgar’s most recent project started when she noticed that some Mnemiopsis could spawn and produce offspring several months earlier in their life cycle than previously reported. This would be like discovering your dog could produce a litter of puppies just weeks after it was born. Intrigued, Edgar asked her lab mates to help her brainstorm possible variables that could explain her observation. Someone mentioned that the air conditioner had broken down, leaving the lab unusually warm.

Knowing that temperature influences the reproduction of other sea creatures, Edgar designed experiments controlling for high and low temperature extremes. While her results suggest that Mnemiopsis yield more offspring at higher temperatures (a result not altogether surprising), temperature alone does not seem to account for the early spawning she observed. The number of animals raised in bowls also does not affect spawning age.

Edgar also considered the role of diet on spawning, focusing on fats and essential fatty acids. She delivers these macronutrients to her young comb jellies using tiny animals called rotifers—after chowing on some rotifers, Mnemiopsis begins to lay eggs. Adequate nutrition seems to be the most significant factor that makes these animals spawn so early.

These results are encouraging. “Needing food to make babies is pretty universal, so these data suggest that Mnemiopsis probably spawns this way regularly,” Edgar said. “This discovery significantly shortens the life cycle for this ctenophore in the laboratory and may reduce the difficulty of raising animals for researchers working inland and without advanced marine facilities. These results are an important step in making this ctenophore more accessible to anyone around the world who wants to study them.”

This is huge news for the science communities outside of Whitney that sometimes focus their research on more familiar organisms like fruit flies or mice. Expanding the research pool to include ctenophores — one of the most ancient animal branches on the evolutionary tree of life — means that scientists can more accurately map the rich biodiversity on the planet, confirming previous theories and illuminating potential exceptions that would otherwise remain hidden.

“I want my research to have an impact on people. Ctenophores are perfect for this because we can use these apparently ‘simple’ animals for insights into environmental challenges and into human health.”

ALLISON EDGAR

“Nature has done millions of successful experiments for us resulting in the diversity of organisms we see around us,” explained Dr. Mark Q. Martindale, director of Whitney Laboratory and principal investigator overseeing Edgar’s research. “It’s really terrific to see clever people studying biodiversity to learn more about how the world works!”

As Edgar continues to explore the mysteries of the comb jellies, she hopes to discover ways that scientists might “turn on” regeneration in species that can no longer regenerate well.

“We’re very grateful to all the sites that allow us to collect animals for this research,” Edgar said. She and her team collect ctenophores in the waters around Whitney campus, as well as from the docks owned by Marker 8 Hotel and Marina on Anastasia Island, the Sunset Inlet Homeowner’s Association in Flagler, the Saint Augustine and the Palm Coast Marinas. You can help with Allison’s research by alerting her team to ctenophore sightings at [email protected].

So next time you see those translucent “jelly balls” floating in the Matanzas Inlet, maybe try imagining that somewhere in those ctenophore cells is a secret that could someday help treat degenerative diseases and other injuries. Or at the very least enjoy one of nature’s living light shows.