- April 26, 2024

-

-

Loading

Loading

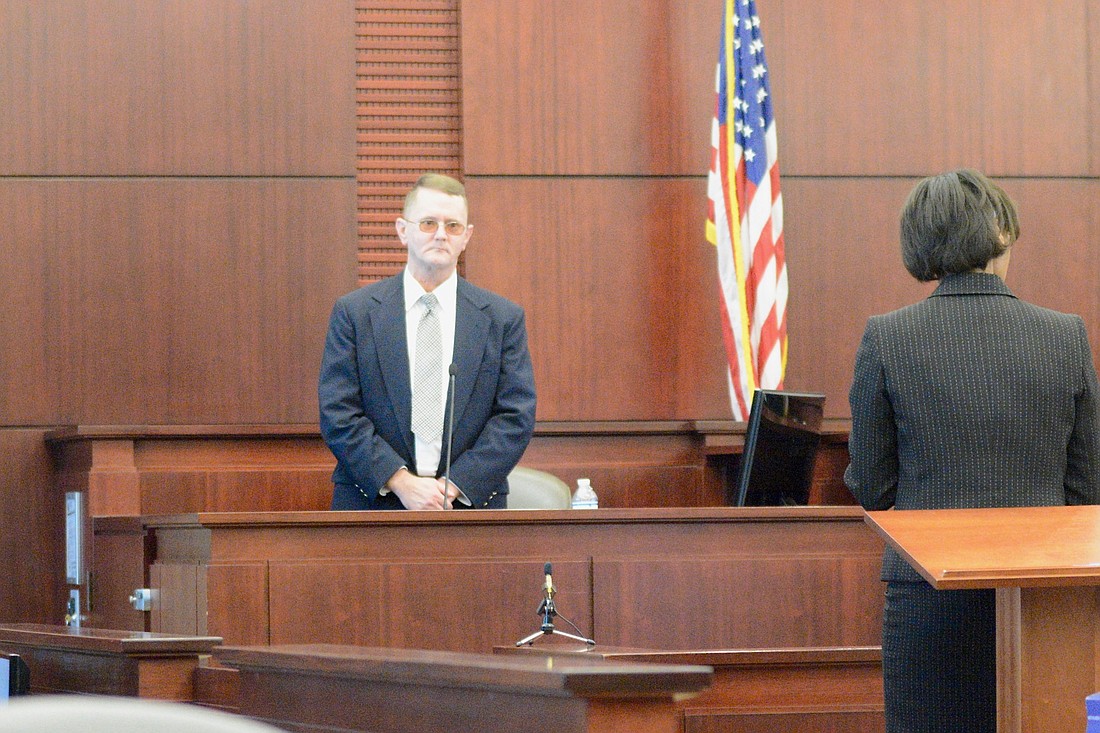

Neither side in the trial of Bruce Haughton, 54, at the county courthouse May 22 argued that Haughton wasn't trying to kill himself when he helped rig a car to feed carbon monoxide back into itself, then got inside the vehicle with his longtime girlfriend to wait for the gas to work.

But Haughton didn't die on that June 30, 2017. His girlfriend, Katherine Goddard, 52, did, and deputies charged Haughton with "assisting self-murder" for his part in their suicide pact.

A jury of two men and four women deliberated for one hour and 49 minutes, then found Haughton guilty. A sentencing hearing will be held before Circuit Judge Terence Perkins at a later date. The trial lasted three days, including jury selection.

Before coming to a verdict, and about an hour and 23 minutes into their deliberations, the jurors had asked two questions of the court:

Question 1: Did the definition of assisting self-murder "require the inclusion of one, some, or all of the defined terms" that were listed in the legal definition of "assisting," which had been defined as "to aid, abet, facilitate, permit, advocate or encourage"?

"In other words, if we feel they only 'permitted' the suicide, would that be enough to be considered 'deliberately assisting?'" the jury asked.

The court instructed the jurors to rely on the definition of "deliberately assisting" that they'd already been provided by the court in their jury instructions.

Question 2: Does the defendant's state of mind factor into of the definition of "deliberately assisting?"

"In other words, if the defendant is not of sound mind, could he be held accountable for deliberately assisting?" the jury asked.

Out of earshot of the jury, the prosecution and defense had disagreed on the answer to that second question: The inclusion of the word "deliberately" in the charge, a defense attorney said, raised the question of state of mind. But the prosecution countered that it didn't rise to the level of a legal defense: Haughton had not entered an insanity defense.

Once again, Circuit Judge Terence Perkins told the jurors to work with the information they had already been given.

For the prosecution, the case was factually simple. The state, Assistant State Attorney Jennifer Dunton said, had to establish just three elements to prove the crime: That Goddard was dead, that she had committed suicide, and that Haughton had assisted her.

And he had: Although he initially told deputies that he didn't remember what had happened, denied involvement in any suicide plot, and said he had not been suicidal, he later admitted to helping tape the garage door closed with duct tape — he taped the top, and she taped the bottom, he said — and to helping affix a dryer duct to the car's exhaust pipe and run it back into the car to return the fumes to the Ford Escort's interior in the garage of their home on Palm Coast's Red Clover Lane.

He'd placed a handgun on the floorboard, in case the gas didn't work — as it hadn't when they'd attempted a similar method with carbon monoxide the day before.

Goddard's daughter had found the couple in the car, unconscious, and called 911, and paramedics were able to revive Haughton, who was hospitalized at Florida Hospital Flagler before deputies took him to jail. Goddard, who had a heart condition that made her more susceptible to the poison, could not be revived.

On the witness stand, questioned by Dunton, Haughton said that Goddard had threatened to kill herself before. Both of them had had chronic pain conditions and had been cut off from the meds by their doctor. Goddard also had bipolar disorder. In the past, he'd disregarded her threats, he said.

Dunton pointed out that he hadn't tried to get her help.

And he'd lied to deputies, she said. In the hospital, Haughton had told deputies that he wasn't suicidal. Haughton, on the witness stand, admitted that that was a lie, and said he'd told it because he didn't want to be involuntarily committed under the state's Baker Act, as he'd been twice in the past.

But defense attorney Rose Marie Peoples said that the case was more complex: What Haughton's true intention was mattered, she said, and his intention was to kill himself.

"What no one is debating is that Bruce Haughton was in that vehicle trying to commit suicide," Peoples said. "Justice is not served or followed if you ignore the fact that he was actively trying to commit suicide, to himself."

Peoples said that it was also clear that Goddard had wanted to die: She was the one who'd written their suicide note, asking that the couple's dogs be cared for. She had helped set up the car.

"He didn’t carry her into the car. He didn’t lift her into the vehicle," Peoples said. "She did that all herself."

Peoples, in her closing argument, showed the jury a photo of Robin Williams, the actor who died by suicide in 2014.

"Sometimes, when we get a picture or a snapshot of individuals, it’s not accurate; we’re not really seeing what’s going on," she said.

Like the deputies who saw Haughton say that he wasn't suicidal: Was it really that hard to understand, she said, "That he felt hopeless? That he didn’t want to expose that hopelessnesss to two officers?"

As to why Haughton hadn't tried to get help for Goddard, she said, he hadn't been in the state of mind to do that.

She displayed a photo from the final scene of the 1991 Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis movie "Thelma & Louise," which ends with the two protagonists, fleeing the law and cornered by officers in their convertible on the edge of the Grand Canyon, deciding to join hands and then floor it, sending the car careening over the side.

The analogy was clear: Haughton and Goddard, Peoples said, had similarly "Acted together. Every action they’re taking is to one cause, one purpose, working together."

But Dunton told the jury that the fact that Haughton and Goddard had worked in concert did not negate Haughton's culpability.

If a mother starves her child to death, and, while doing so, also herself stops eating, would she therefore not be guilty in her child's death, Dunton asked?

"Deliberately assisting someone else and yourself is not mutually exclusive," Dunton said. "There is not an exception and a carveout under the law."